Frailty in older adults is a clinically recognized syndrome that highlights a decline in physiological reserves and resilience. As the population ages, understanding frailty—and especially approaches for preventing frailty—has never been more critical. This article provides an evidence-based exploration of frailty in aging, its underlying causes, and practical strategies for prevention, including emerging insights on peptides for aging and hormonal therapies.

What Is Frailty in Older Adults?

Frailty is more than just feeling weak with age; it’s a dynamic state of decreased strength, endurance, and physiological function that increases vulnerability to negative health outcomes. Frail older adults are at a higher risk for falls, disability, hospitalizations, and mortality even after minor stressors like infections or minor surgery.

Key Criteria for Frailty

Commonly, frailty is identified using the following features:

- Unintentional weight loss (often more than 5% of body weight in a year)

- Muscle weakness (measurable by grip strength)

- Self-reported exhaustion

- Slow walking speed

- Low physical activity

Individuals meeting three or more of these criteria are often classified as frail; one or two criteria imply a pre-frail state.

Causes of Frailty in Older Adults

Frailty is driven by multifactorial, interconnected processes. Biological aging, chronic diseases, infections, and lifestyle factors all contribute. Here is a breakdown of the main drivers:

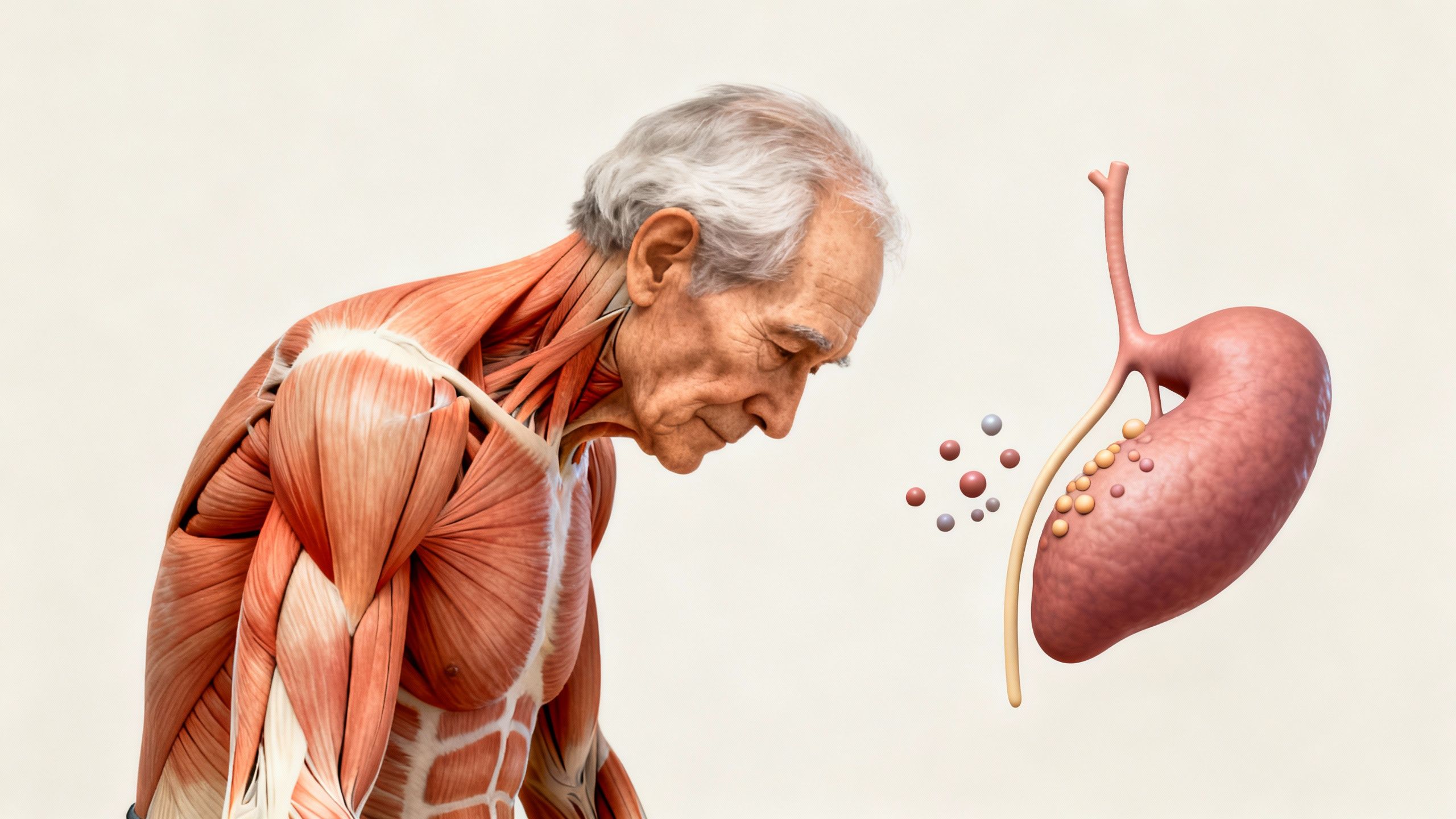

Age-Related Muscle Loss (Sarcopenia)

Loss of muscle mass and function, termed sarcopenia, is a central component of frailty. Its causes include:

- Decreased physical activity

- Imbalance between anabolic (muscle-building) and catabolic (muscle-breakdown) hormones

- Chronic inflammation

- Malnutrition

Chronic Disease

Conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney dysfunction, and lung disorders accelerate the decline in physiological reserves.

Hormonal Changes

Sex hormone levels, growth hormone, and other anabolic hormone levels drop with age, contributing to muscle weakness and functional decline.

Inflammation and Oxidative Stress

Low-grade, chronic inflammation—sometimes called “inflammaging”—alters muscle metabolism, fuels sarcopenia, and impairs recovery.

Nutritional Deficiency

Deficiencies in protein, vitamin D, antioxidants, and other nutrients directly impair muscle and overall function, increasing frailty risk.

Physical, Cognitive, and Social Impact

Frailty can have a wide-reaching impact beyond physical weakness:

- Reduced mobility and independence

- Increased cognitive decline risk

- Higher rates of depression and social isolation

- Frequent hospitalizations and longer recovery times

Mechanisms Underlying Frailty

Due to the complexity of aging, multiple intertwined mechanisms underlie frailty:

Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Aging mitochondria produce less energy and more oxidative byproducts, reducing cellular function—a prominent factor in muscle weakness and fatigue.

Dysregulated Hormone Pathways

Insulin, growth hormone, testosterone, and estrogen all play vital roles in muscle anabolism and tissue repair. Their age-related decline impairs resilience.

Chronic Inflammatory State

Increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-alpha) are linked to muscle catabolism and decreased strength in frail individuals.

Impaired Protein Synthesis

Age and inactivity lower the body’s ability to synthesize new muscle protein, leading to progressive muscular atrophy.

Key Mechanisms Table

| Mechanism | Impact on Frailty |

|---|---|

| Mitochondrial decline | Decreased muscle energy, endurance |

| Hormonal decline | Weakened tissue repair, decreased muscle |

| Chronic inflammation | Increased muscle breakdown |

| Protein synthesis drops | Progressive loss of muscle mass |

| Nutritional deprivation | Reduced muscle repair and function |

Preventing Frailty: Evidence-Based Strategies

Thankfully, frailty is not inevitable. Proactive interventions can prevent or even partially reverse frailty, particularly when started before major functional decline occurs.

1. Exercise: The Foundation

- Progressive resistance training (weight-bearing or elastic bands): increases muscle strength and mass

- Aerobic exercises (walking, cycling): improves cardiovascular health and endurance

- Balance and flexibility work (yoga, tai chi): reduces fall risk

Key Exercise Tips

- Individualize programs to ability level

- Aim for at least 2 strength sessions and 150+ minutes of moderate activity weekly

- Supervised group classes can enhance adherence and motivation

2. Optimal Nutrition

- Prioritize high-quality protein intake (at least 1–1.2g/kg body weight per day)

- Ensure adequate calories to prevent unintended weight loss

- Vitamin D and calcium may support muscle and bone health

- Address micronutrient deficiencies (vitamin B12, iron, antioxidants)

3. Managing Chronic Conditions

- Tight control of chronic diseases (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, renal impairment)

- Regular medication reviews to avoid unnecessary drugs that may impact function

4. Social Engagement and Cognitive Health

- Encourage regular social interaction to reduce isolation which can worsen frailty

- Cognitive training and participation in community activities maintain both mind and body

5. Novel Compounds: Peptides and Hormonal Therapies

Emerging therapies are under research for their potential to target underlying mechanisms of frailty. While human studies are ongoing and safety remains a paramount concern, several promising approaches include:

Peptides in Aging

- BPC-157: This stable gastric peptide is being explored for effects on tissue repair, inflammation, and recovery. Though most studies are preclinical, it is hypothesized to encourage healing and potentially improve muscle function in older adults.

- MOTS-c: A mitochondrial-derived peptide, MOTS-c has shown early promise in human pilot studies for boosting metabolic health, muscle and endurance in the context of age-related decline. Emerging research suggests it could play a role in preventing frailty by enhancing mitochondrial resilience.

Hormonal Therapies

- Testosterone therapy: For selected older adults with clear deficiency and symptoms, testosterone therapy may improve muscle mass and strength. However, the risks and benefits in older populations must be carefully weighed.

Caution: Hormonal and peptide therapies are not universally recommended. They require individualized risk–benefit assessment, supervised administration, and more robust long-term evidence.

Practical Applications: Individual Variation and Realistic Goals

Preventing frailty in older adults is not a one-size-fits-all process. Interventions must be tailored to the individual’s current health status, mobility, comorbidities, and personal goals. While some may restore significant function with intensive intervention, others may benefit most from maintaining independence and quality of life.

Setting Realistic Expectations

- Improvement is possible at any age, even in those already categorized as frail

- Focus on small, consistent changes in activity, diet, and engagement

- Multidisciplinary care teams (physician, nutritionist, physiotherapist, occupational therapist) can provide holistic support

Red Flags for Rapid Intervention

- Sudden, unintended weight loss

- New or worsening weakness, falls

- Onset of confusion or functional decline

Immediate evaluation and tailored intervention can significantly improve outcomes.

Future Directions in Frailty Research

Rapid progress is being made toward understanding how to detect, treat, and even prevent frailty more effectively:

- Precision medicine: Genetic and biomarker testing may soon help identify those at highest risk and enable individually optimized interventions

- Integrative therapies: Multi-component programs combining exercise, nutrition, cognitive training, and selected pharmacological support are under investigation

- Advanced imaging and digital tools: Wearables and AI may soon help monitor changes in mobility and detect pre-frailty earlier

Conclusion: The Path Forward in Preventing Frailty

Frailty in older adults represents a critical turning point for health, independence, and quality of life. Proactive, multifaceted approaches—including tailored exercise, optimized nutrition, management of chronic diseases, and the cautious investigation of novel compounds such as peptides for aging—offer promising strategies for both preventing and managing this syndrome. Staying up-to-date with emerging science and working closely with healthcare teams can empower older adults to remain stronger, more resilient, and independent for longer.

Studies / References

1. Fried LP, et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/

2. The Effect of Exercise Program Interventions on Frailty in Older Adults:

A Systematic Review.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39518709/

3. Protein Supplementation and Exercise for Sarcopenia and Physical Frailty:

A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39955964/

4. Frailty and Testosterone Level in Older Adults:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.