Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the leading causes of vision loss among adults over the age of 50. As the name suggests, AMD predominantly affects the macula, the part of the retina responsible for sharp central vision. The progression of AMD often leads to significant visual impairment, impacting quality of life and independence.

This article provides an in-depth overview of the mechanisms, causes, and risk factors behind age-related macular degeneration, leveraging the latest human research to inform prevention and management strategies.

What Is Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)?

AMD refers to a group of degenerative retinal disorders primarily impacting the macula. The macula is a small region at the center of the retina, crucial for high-resolution visual tasks like reading and recognizing faces. AMD gradually destroys photoreceptor cells, leading to blurry or distorted central vision.

Key facts about AMD:

- Affects approximately 150 million people globally

- Rare before age 50; risk rises significantly with advancing age

- Two forms: dry (atrophic) and wet (neovascular)

Types of Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Dry (Atrophic) AMD

- Accounts for 80–90% of cases

- Gradual accumulation of drusen (lipid-protein deposits) under the retina leads to thinning and cell death

- Usually slower vision loss compared to wet AMD

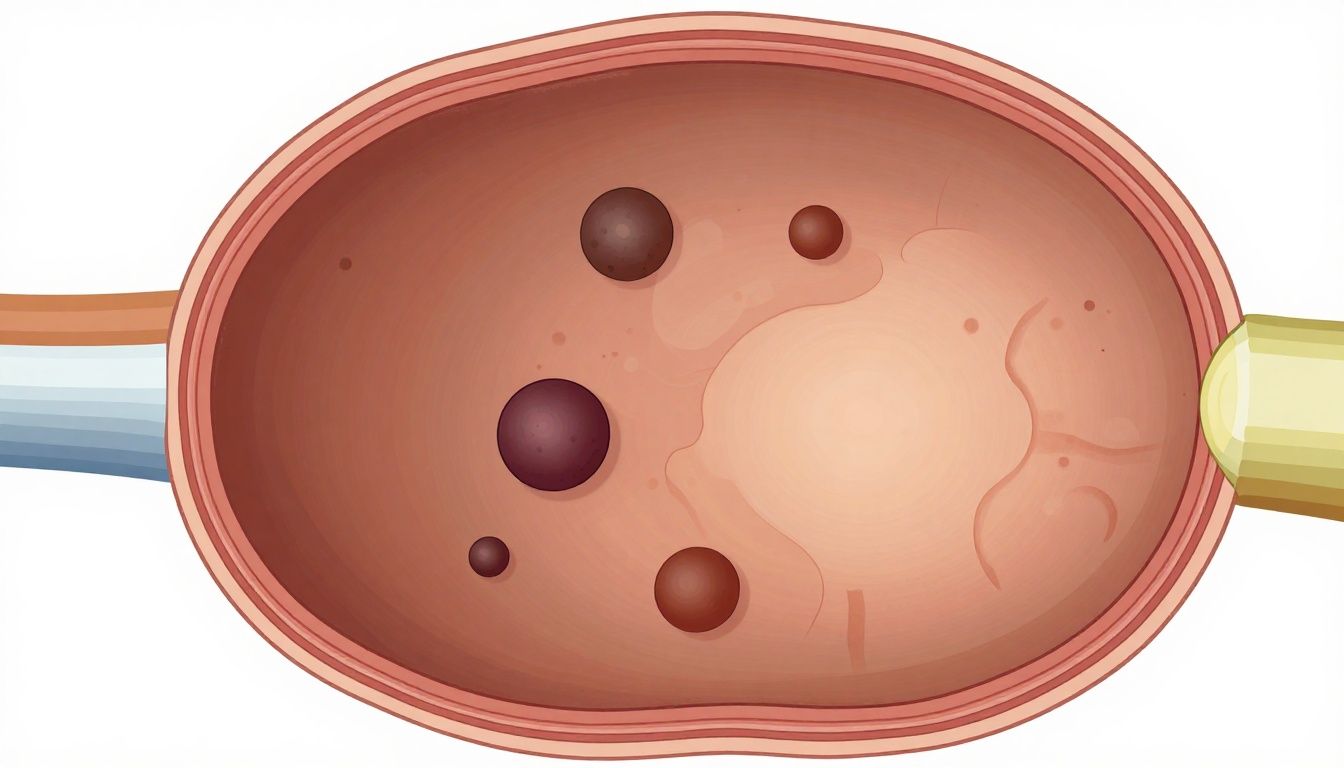

Wet (Neovascular or Exudative) AMD

- 10–20% of all AMD but responsible for most severe vision loss

- Abnormal new blood vessels grow beneath the retina, leak fluid/blood, causing rapid and irreversible damage

AMD is a progressive disease, and early detection is crucial for optimal management.

Mechanisms of Retinal Aging and Degeneration

The retina, and specifically the macula, is highly metabolically active and vulnerable to age-related changes:

- Oxidative stress: The retina’s high oxygen use makes it particularly susceptible to oxidative damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- Lipid and protein accumulation: Waste products such as drusen collect beneath the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), impairing its function.

- Inflammation: Chronic, low-grade inflammation amplifies cellular damage and disrupts retinal integrity.

- Vascular compromise: With advancing age, blood flow to the retina declines, reducing oxygen and nutrient delivery.

These intertwined processes contribute cumulatively to the gradual loss of photoreceptor cells, paving the way for the development of AMD.

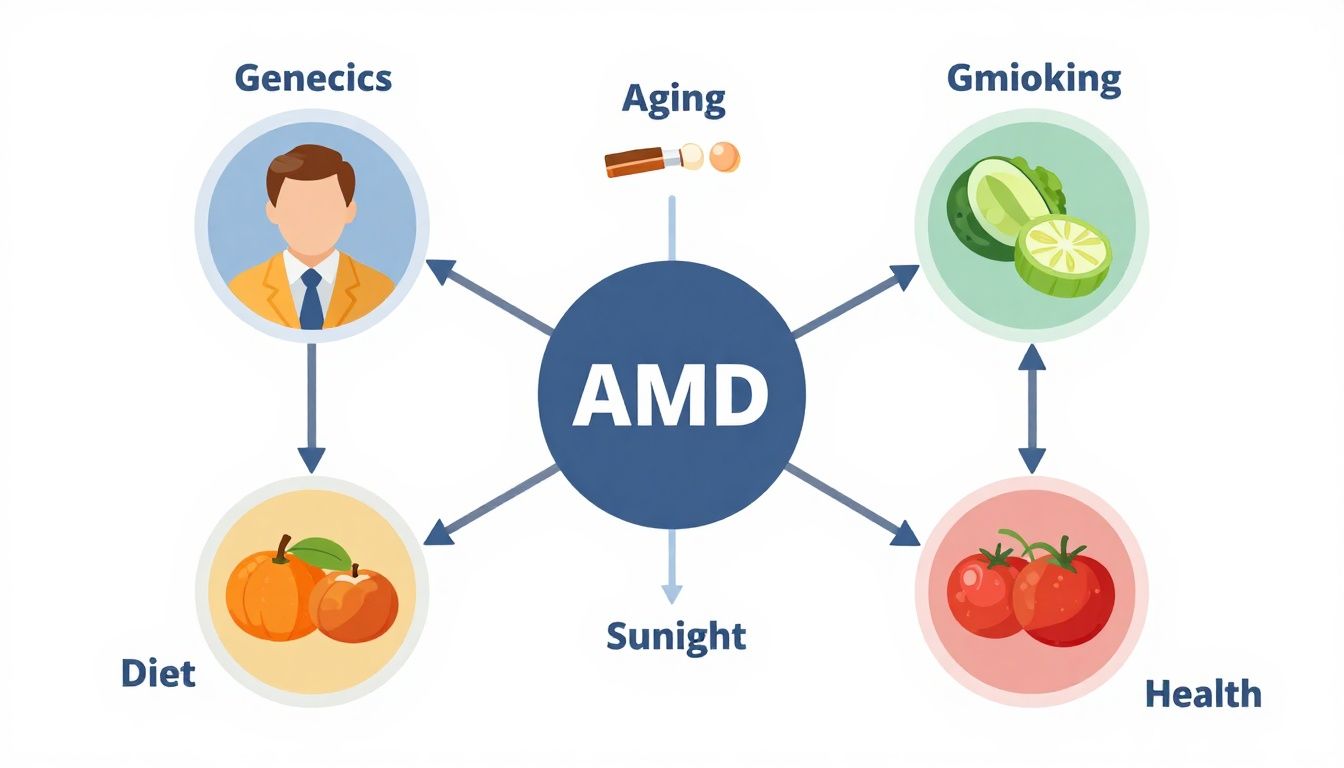

Major Causes of Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Understanding the origins of AMD requires exploring both genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures:

Genetic Factors

- Family history: Individuals with first-degree relatives affected by AMD are at higher risk.

- Key genes: Polymorphisms in CFH, ARMS2, HTRA1, and C3 genes are strongly associated with AMD risk.

- Ethnicity: AMD prevalence is higher among people of European descent.

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers

- Smoking: The single most consistently proven non-genetic risk factor; it doubles the risk of developing AMD.

- Diet: Diets low in antioxidants (vitamin C, E, zinc, lutein, zeaxanthin) and high in saturated fats may accelerate retinal aging.

- Sunlight exposure: Excessive lifetime exposure to UV and blue light can contribute to cumulative retinal damage.

Age and Other Systemic Factors

- Advancing age: AMD risk rises markedly every decade after age 50, with an exponential increase for those over 75.

- Hypertension and cardiovascular disease: Vascular health directly impacts retinal function.

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome: Associations with oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation heighten risk.

AMD Causes and Risk Factors: A Closer Look

1. The Central Role of Aging

The retina undergoes significant structural and functional declines with age, such as:

- Thinning of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)

- Reduced choroidal blood flow

- Declining mitochondrial function and energy production

These changes make the macula more vulnerable to secondary insults from genetics or the environment, establishing age as the primary driver of disease.

Key point: Retinal aging alone explains the steep risk curve for AMD later in life, especially when paired with modifiable lifestyle risks.

2. Genetics and Family History

- People carrying high-risk variants in CFH or ARMS2 face up to a 3–8 times greater chance of developing AMD.

- Those with affected siblings or parents have a doubled risk, independent of other factors.

- Ongoing genome-wide association studies continue to identify new risk loci, suggesting a complex, polygenic inheritance.

3. Smoking and Oxidative Stress

- Cigarette smoke introduces free radicals and reduces blood flow, accelerating retinal injury and drusen formation.

- Studies show both current and former smokers are at consistently higher risk; the effect persists even decades after cessation.

- Smoking cessation remains fundamental in reducing AMD incidence and slowing progression.

4. Diet, Nutrients, and Retinal Resilience

- Antioxidant nutrients (lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamins C/E, zinc) help counter oxidative stress and support retinal photoreceptors.

- AREDS (Age-Related Eye Disease Study) formulations slow progression in moderate AMD, though do not prevent its onset.

- Diets rich in leafy greens, colorful vegetables, and healthy fats may confer modest protection.

Table: Dietary Factors and AMD Risk

| Food/Nutrient | Effect on AMD Risk |

|---|---|

| Leafy greens (lutein) | Protective |

| Fatty fish (omega-3s) | Mildly protective |

| Saturated/trans fats | Increases risk |

| Processed foods | Increases risk |

| High-glycemic carbs | Increases risk |

Additional Risk Factors: The Broader Picture

- Sunlight/UV exposure: While excessive direct sunlight can be hazardous, the lifetime impact is likely less than other major factors. Regular sunglasses use is supported.

- Diabetes: Combined effects of high blood sugar and vascular compromise may modestly increase AMD risk.

- Low physical activity: Sedentary lifestyles contribute to several modifiable risk factors (obesity, vascular disease).

Individual Variability in AMD Risk

Not everyone exposed to the same risk factors develops AMD. Individual susceptibility depends on genetic makeup, health status, environmental exposures, and chance. This means personalized prevention strategies are most effective:

- Genetic testing may identify highest-risk individuals

- Family history informs early, frequent eye exams

- Attention to cardiovascular and metabolic health supports retinal function

Research Context: Key Milestones in AMD Understanding

1. AREDS and AREDS2 (Large-Scale Human Trials)

- Identified benefit of specific antioxidant/zinc supplementation in reducing progression in intermediate-to-advanced AMD

2. Genome-wide Association Studies

- Ongoing discoveries of heritable risk alleles

- Clarified different risk profiles for dry vs. wet AMD

3. Smoking and AMD Meta-Analysis

- Conclusive human data linking tobacco use to elevated AMD risk

4. Lifestyle and Diet Intervention Studies

- Modest benefits from anti-inflammatory, Mediterranean-type diets

Practical Applications: Reducing Your AMD Risk

Actionable steps based on human research:

- Regular dilated eye exams: Begin by age 40—sooner with risk factors.

- Quit smoking: The most impactful lifestyle change.

- Eat a nutrient-rich diet: Focus on dark leafy greens, orange/yellow vegetables, omega-3 fats.

- Control blood pressure and systemic conditions: Cardiovascular risk management supports eye health.

- Wear UV-protective sunglasses: Especially if spending large amounts of time outdoors.

- Maintain healthy body weight and stay active.

- Consider AREDS2 supplements: For those with moderate-to-advanced AMD, after medical consultation.

Looking Forward: Prevention and Early Detection

With an aging population, preventing and slowing the progression of AMD is increasingly vital. Comprehensive strategies blend genetic insight, lifestyle modification, and early intervention. Age-related macular degeneration research continues to inform best practices for preserving sight and reducing the global burden of vision loss.

Studies / References

- AREDS Report No. 8 (2001)

- AREDS2 (2013), Randomized Controlled Trial

- Meta-analysis: Smoking and AMD (2006, Thornton et al.)

- Genome-wide Association Study of AMD (Fritsche et al., 2016, NEJM)

- Retinal Aging and Dietary Patterns (Merle et al., 2019)

Conclusion: Takeaway Messages on AMD Causes and Prevention

Age-related macular degeneration is driven by a complex interplay of aging, genetic susceptibility, and lifestyle factors. While not all risk factors are controllable, significant measures—like quitting smoking, nourishing the retina with antioxidants, and regular ophthalmologic monitoring—can effectively reduce the risk and slow disease progression. Ongoing research in genetics and personalized prevention offers hope for earlier detection and novel interventions in retinal aging.

This article is for information purposes only. Consult an eye care professional for personalized medical advice if you suspect changes in your vision or have risk factors for AMD.