Cellular senescence is emerging as a fundamental biological process intimately linked to aging, tissue degeneration, and chronic diseases. Over the past decade, researchers have made significant strides in deciphering the mechanisms driving cellular senescence and exploring targeted interventions—ranging from peptides to senolytic compounds—to delay or reverse age-associated pathology.

In this article, we’ll explore the biology of cellular senescence, its role in age-related degeneration, and the most promising anti-aging interventions. We’ll dissect the latest human research and discuss real-world implications for healthy aging.

Five Key Insights on Cellular Senescence and Aging

- Cellular senescence increases with age and contributes to tissue degeneration

- SASP drives chronic inflammation and disrupts tissue repair

- Senescent cells impair stem cell and regenerative function

- Senolytic therapies show early promise but remain experimental in humans

- Lifestyle factors influence the accumulation and clearance of senescent cells

What Is Cellular Senescence?

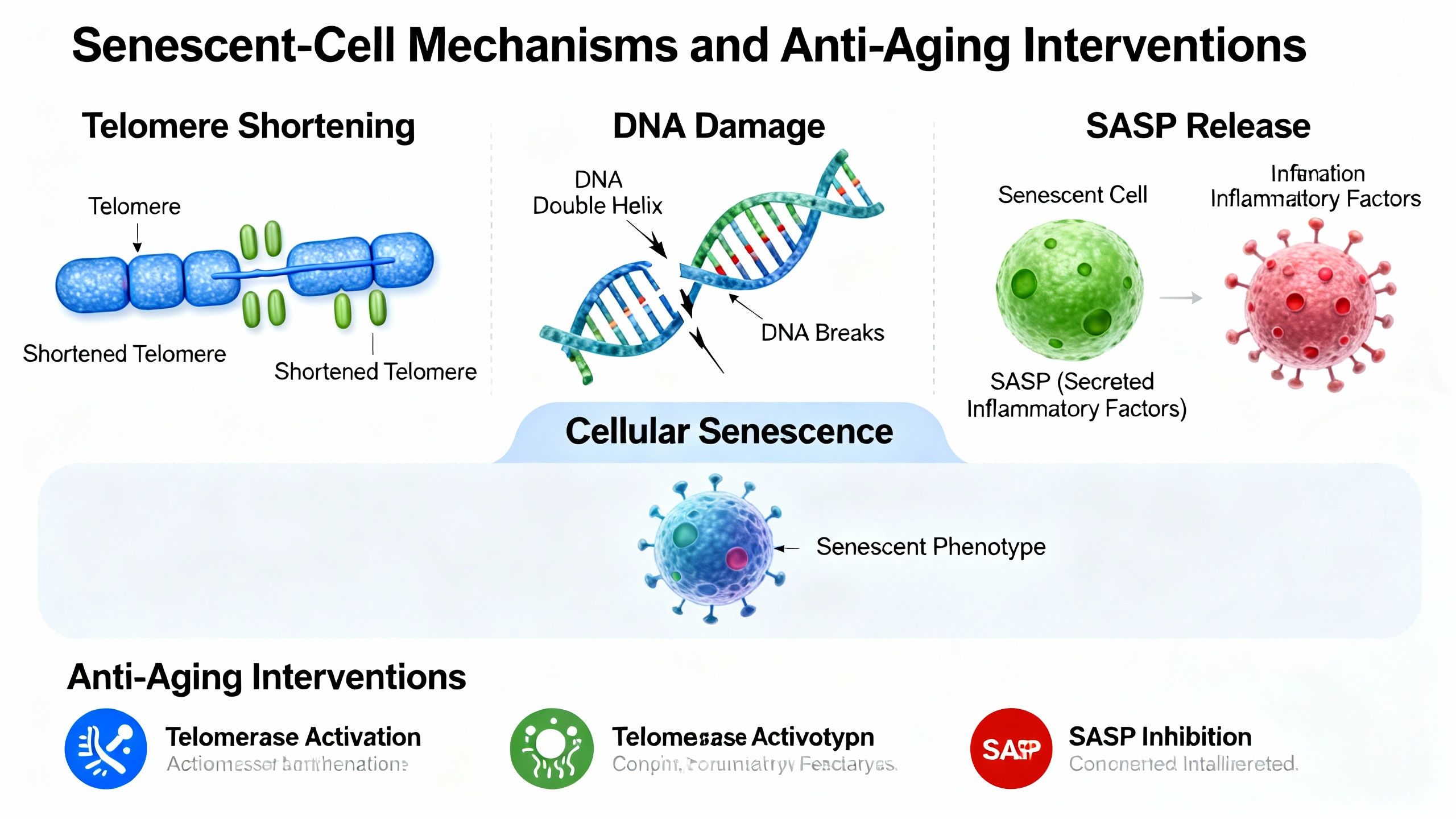

Cellular senescence refers to a state in which normal cells lose their ability to divide and function, yet remain metabolically active. These cells develop a distinctive phenotype, characterized by:

- Permanent cell-cycle arrest (no proliferation)

- Changes in cellular morphology

- Metabolic reprogramming

- Secretion of inflammatory factors known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)

Senescent cells are initially thought to play protective roles (e.g., wound healing, tumor suppression) but, with aging, their accumulation is closely tied to tissue dysfunction and degeneration.

Triggers of Senescence: Why Do Our Cells Stop Dividing?

Multiple stressors and events can push a cell into senescence:

- Telomere shortening: Each cell division erodes telomeres, the chromosome-protecting caps, eventually triggering senescence

- DNA damage and genomic instability: Radiation, oxidative stress, mutations

- Oncogene activation: Abnormal signals from mutated genes

- Mitochondrial dysfunction: Compromised cellular energy production

- Chronic inflammation

This process is highly regulated by pathways involving p53, p21, and p16INK4a, acting as cellular guardians.

The Good, the Bad, and the Accumulation: Senescence in Aging

Senescent cells perform beneficial functions in youth, halting the growth of potentially cancerous cells and aiding in tissue repair. However, over decades, the balance tilts:

- Senescent cell clearance becomes less efficient with age

- Accumulated cells secrete pro-inflammatory factors (SASP)

- This environment promotes tissue degeneration, stem cell dysfunction, and chronic diseases

Key tissues impacted:

- Skin (wrinkling, poor wound healing)

- Muscle (sarcopenia, weakness)

- Joint cartilage (osteoarthritis)

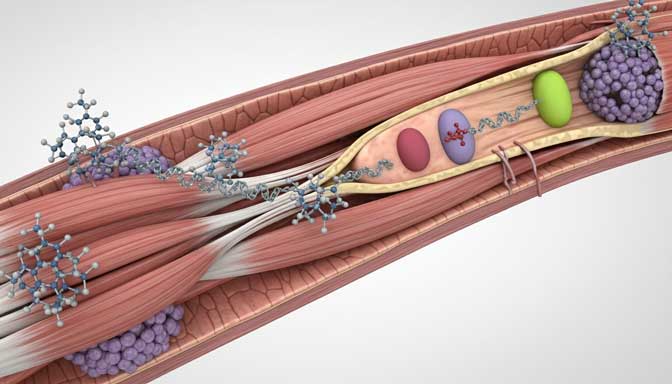

- Blood vessels (atherosclerosis, frailty)

- Eye, brain, liver, and more

Peptides, Senolytics, and Anti-Aging Interventions

Peptides in Targeting Senescence

Recent attention has focused on peptides with potential anti-senescence effects, notably Epitalon. Peptides may support telomere maintenance, regulate stress responses, or modulate inflammatory signaling. While research is early, their mechanism is of great interest—especially in the sphere of peptides senescence interventions.

Epitalon

- A synthetic version of the pineal peptide Epithalamin

- Shown to lengthen telomeres and modulate aging pathways in animal studies; early human trials are ongoing

- Potential benefits: improved sleep, immune modulation, possible extension of healthspan (human data limited)

Senolytic Compounds

Senolytics are molecules that selectively “clear out” senescent cells:

- Dasatinib & Quercetin: The most studied human combination; shown in pilot clinical trials to reduce senescent cell burden and improve some physical function markers in older adults

- Fisetin: A plant polyphenol under investigation for its senolytic and anti-inflammatory properties

- Navitoclax: An anti-cancer agent that has senolytic effects, but with notable side effects limiting current clinical application

The rise of senolytic therapies is redefining anti-aging interventions for those seeking evidence-based strategies.

Mechanisms: How Cellular Senescence Drives Degeneration

Senescent cells impair tissue integrity via several key mechanisms:

1. Pro-Inflammatory Secretions (SASP):

- Release of cytokines, chemokines, and proteases

to local tissue - Recruit immune cells, promote chronic inflammation, and damage neighboring healthy cells

2. Tissue Remodeling and Stem Cell Impairment:

- Excess matrix-degrading enzymes (like MMPs) weaken tissue structure

- Inhibit local stem/progenitor cell functions, reducing tissue repair capacity

3. Altered Extracellular Signaling:

- Disruption of normal communication between cells in organs or tissues

Senescence is not confined to any one tissue – its systemic actions are why it’s termed the “root of age-related degeneration.”

How Do We Measure Cellular Senescence in Humans?

Though easily modeled in the laboratory, quantifying senescence in living humans is complex. Methods include:

- Biopsy and staining (e.g., SA-β-galactosidase): Direct but invasive

- Molecular markers: p16INK4a, p21, and SASP profile in blood or tissues

- Functional assays: Muscle strength, skin elasticity, wound healing rates (indirect)

Advances in noninvasive biomarkers are crucial to tracking the impact of anti-aging interventions in clinical studies.

Disease Associations: Senescence in Chronic Conditions

The chronic accumulation of senescent cells is implicated in many common age-related disorders, including:

- Osteoarthritis: Promotes joint cartilage breakdown

- Type 2 Diabetes: Impairs beta-cell and adipose tissue function

- Atherosclerosis: Triggers vascular inflammation

- Neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s): SASP contributes to neuroinflammation

- Frailty and muscle loss (sarcopenia): Impacts muscle progenitor cell function

By targeting senescent cells, we may be able to delay or minimize these multifaceted degenerative changes.

Anti-Aging Interventions: Human Evidence So Far

While animal and cell research has exploded, human clinical trials in cellular senescence and aging remain in early stages. Key interventions studied include:

Lifestyle and Non-Pharmacological Approaches

1. Nutritional interventions:

- Caloric restriction and fasting-mimicking diets can reduce senescent cell burden in animal studies; human data suggest possible moderation of aging markers

2. Regular exercise:

- Maintains mitochondrial health and may enhance immune clearance of senescent cells

3. Stress reduction and sleep hygiene:

- Chronic inflammation, poor sleep, and stress hasten senescence

Targeted Pharmacological & Peptide Interventions

- Senolytic Trials: Small pilot studies of dasatinib + quercetin in older adults and those with chronic diseases show improvements in some functional and biological markers; safety and long-term effects are not yet well-defined.

- Epitalon: Early-stage Russian trials in older adults suggest improved markers of physiological aging, but replication in larger, Western studies is lacking.

- Fisetin and other flavonoids: Currently under investigation in human aging and disease models.

For a broader perspective, see our summary of clinical trials in age-related degenerative conditions.

Safety Concerns and Individual Variability

Caution is warranted:

- Clearing too many senescent cells too quickly may impair beneficial functions and recovery

- Senolytic drugs can have side effects (e.g., blood disorders with navitoclax)

- Peptide therapies are still experimental, and regulatory status varies widely across regions

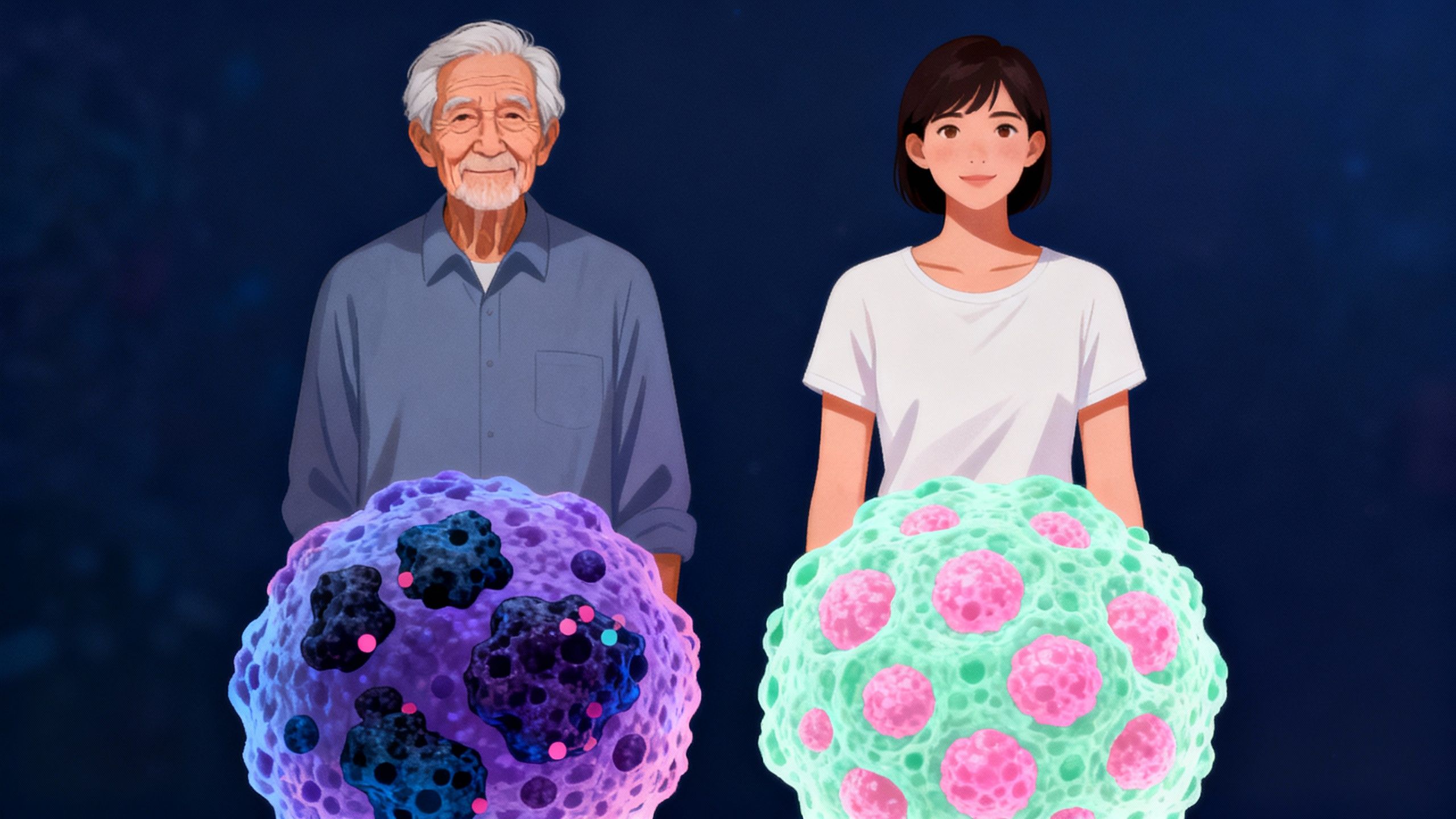

Personalized approaches are essential. Lifestyle factors, genetics, and underlying disease all influence an individual’s balance of beneficial versus detrimental senescence.

Practical Applications and Future Directions

As research advances, practical, evidence-based interventions may soon be possible to reduce the burden of senescent cells:

- Routine exercise, healthy eating, and stress management remain core recommendations for healthy aging

- Pharmacological interventions (senolytics, peptides) are advancing towards more targeted, less toxic, and more personalized therapies

- Regular clinical monitoring for markers of inflammation and senescence may help identify at-risk individuals earlier

The future: Senescence-targeting anti-aging interventions may ultimately help reduce multimorbidity, improve functional status, and enhance quality of life as we age.

Studies / References

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23746838/ - Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(9):729–740.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17944085/ - Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: preliminary report from a clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:446–456.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31542391/ - Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Senolytic drugs: from discovery to translation. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2020;288(5):518–536.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32686219/ - Araj SK, et al. Overview of Epitalon—A pineal tetrapeptide with geroprotective potential. Biomedicines. 2023;11(2):472.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11943447/

Conclusion: Cellular Senescence as a Target in Modern Aging Science

Research into cellular senescence is rapidly redefining our understanding of aging and age-related degeneration. While the field is young, emerging interventions—including peptides senescence, novel senolytic compounds, and practical lifestyle changes—hold enormous promise for extending healthspan.

However, all interventions must be evaluated with careful attention to individual variability, long-term safety, and robust human research.

Key Takeaway: Cellular senescence is both a root cause and a promising therapeutic target for the diseases and degeneration of aging. Strategic interventions may one day help us age with greater health, function, and vitality.